- Home

- Martin Greenberg

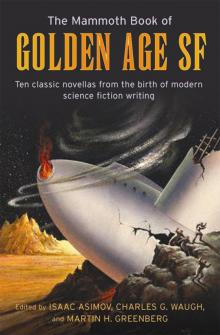

The Mammoth Book of Golden Age SF

The Mammoth Book of Golden Age SF Read online

ISAAC ASIMOV was for five decades a central figure in science fiction writing. Born in the Soviet Union and raised in Brooklyn, he wrote over 330 books.

CHARLES G. WAUGH is a leading authority on science fiction and fantasy.

MARTIN H. GREENBERG has been called the king of anthologists, with more than one thousand anthologies.

Also available

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica 5

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 17

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction 19

The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Dirty, Sick, X-Rated & Politically Incorrect Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Famous Trials

The Mammoth Book of Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Great Detective Stories

The Mammoth Book of Great Inventions

The Mammoth Book of Hard Men

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Egypt

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Rome

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Battles

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: World War I

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: World War II

The Mammoth Book of Illustrated True Crime

The Mammoth Book of International Erotica

The Mammoth Book of IQ Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Kakuro, Worduko and Super Sudoku

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of On the Edge

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Perfect Crimes and Locked-Room Mysteries

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Roman Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of SAS & Special Forces

The Mammoth Book of Secret Codes and Cryptograms

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock ’n’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Shipwrecks & Sea Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Short Erotic Novels

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Space Exploration and Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Special Ops

The Mammoth Book of Sudoku

The Mammoth Book of True Crime

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampires

The Mammoth Book of Vintage Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Wild Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Women’s Fantasies

The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries

THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF

GOLDEN AGE

SCIENCE FICTION

Edited by Isaac Asimov, Charles G. Waugh

and Martin H. Greenberg

ROBINSON

London

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson Publishing, 1989

This edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2007

Copyright © Nightfall Inc., Charles G. Waugh and

Martin H. Greenberg 1989, 2007

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-1-84529-096-2

ISBN-10: 1-84529-096-8

eISBN: 978-1-78033-723-4

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

Isaac Asimov

TIME WANTS A SKELETON

Ross Rocklynne

THE WEAPONS SHOP

A.E. van Vogt

NERVES

Lester del Rey

DAYMARE

Fredric Brown

KILLDOZER!

Theodore Sturgeon

NO WOMAN BORN

C.L. Moore

THE BIG AND THE LITTLE

Isaac Asimov

GIANT KILLER

A. Bertram Chandler

E FOR EFFORT

T.L. Sherred

WITH FOLDED HANDS

Jack Williamson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ross Rocklynne – Copyright 1941 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1969. Reprinted by permission of the author’s agent, Forrest J. Ackerman, 2495 Glendower Ave., Hollywood, CA 90027.

A. E. van Vogt – Copyright 1942 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1970 by A. E. van Vogt. Reprinted by permission of Richard Curtis Associates, Inc.

Lester del Rey – Copyright 1942 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1970 by Lester del Rey. Reprinted by permission of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10022.

Fredric Brown – Copyright 1943 by Standard Magazines, Inc.; renewed © 1971 by Fredric Brown. Reprinted by permission of Roberta Pryor Inc.

Theodore Sturgeon – Copyright 1944 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1972 by Theodore Sturgeon. Reprinted by permission of Kirby McCauley, Ltd.

C. L. Moore – Copyright 1944 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1972 by Catherine Reggie. Reprinted by permission of Don Congdon Associates, Inc.

Isaac Asimov – Copyright 1944 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1972 by Isaac Asimov. Reprinted by permission of the author.

A. Bertram Chandler – Copyright 1945 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1973 by A. Bertram Chandler. Reprinted by permission of the agents for the author’s Estate, the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10022.

T. L. Sherred – Copyright 1947, renewed © 1975 by T. L. Sherred. Reprinted by permission of the author’s Estate and the author’s agent, Virginia Kidd.

Jack Williamson – Copyright 1947 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc.; renewed © 1975 by Jack Williamson. Reprinted by permission of the Spectrum Literary Agency.

INTRODUCTION

“THE AGE OF CAMPBELL”

Isaac Asimov

In the first book of the series, which dealt with classic science fiction (s.f.) novellas of the 1930s, I said that the 1930s was the decade in which science fiction found its voice. Toward the end of that decade, the voice began to resemble, more and more, that of John Wood Campbell, Jr., and in the 1940s, J.W.C. dominated the field to the point where to many he seemed all of science fiction.

It was a phenomenon that had never happened before and can never be repeated. Before the 1940s, science fiction was so small a field that, in a way, there was nothing to dominate. Hugo Gerns-back had been important in the 1920s, but he was alone. F. Orlin Tremaine had been important in the 1930s, but he did not drown out the other

voices completely.

Campbell, however, towered. He had a charismatic personality that utterly dominated everyone he met. He overflowed with energy and he had his way with science fiction. He found it pulp and he turned into something that was his heart’s desire. He then made it the heart’s desire of the reader.

To put it another way, he found science fiction a side-issue written by eager fans with only the beginnings of ability, or by general pulp writers who substituted spaceships for horses, or disintegration rays for revolvers, and then wrote their usual stuff. Campbell put science fiction center stage and made it a field that could be written successfully only by science fiction writers who had learned their craft.

To put it still another way, he found science fiction a trifling thing that could only supply writers with occasional pin-money and he labored to make of it something at which science fiction writers could make a living. He could not, in the 1940s, drag the field upward to the point of making writers rich, but he laid the foundations for the coming of that time in later decades.

It is impossible for anyone ever to repeat the feat of John W. Campbell, Jr. For one thing you cannot lay the foundations for quality science fiction a second time. The foundation is there for all time and it was laid by Campbell. For another thing, the field has grown to such a pitch (thanks to Campbell) that it is too large ever to be dominated by one man. Even Campbell, larger than life though he was, if he were miraculously brought back into existence, could not dominate the field today.

So who was John Campbell? He was born in Newark, New Jersey on June 8, 1910. I have never found out much about his childhood, except that I received the impression that it was a very unhappy one. He attended M.I.T. between 1928 and 1931, but never finished his schooling there. The story I heard was that he couldn’t pass German. He transferred to Duke University.

This double experience at college was reflected in his later work. At M.I.T. he picked up his interest in science. At Duke, where R.B. Rhine was conducting his dubious experiments on extra-sensory perception, he picked up his interest in the scientific fringe. In the 1940s, science dominated Campbell’s mind, and in the 1950s the scientific fringe did. He went from M.I.T. to Duke in science fiction as well as in his college training. In this volume, however, we are concerned with his earlier phase.

He sold his first science fiction story while he was still a teenager (not unusual among the true devotees) but he was too inexperienced to keep a carbon and T. O’Conor Sloane of Amazing Stories lost the manuscript (which was unusual). It was Campbell’s second sale, then, that marked his first actual appearance. This was “When the Atoms Failed” in the January 1930, Amazing. He was still only nineteen at the time.

In those days, the greatest name among the science fiction writers was E.E. Smith, Ph.D., who had climbed to fame with his “The Skylark of Space”, a three-part serial that appeared in the August, September, and October 1928 issues of Amazing. “The Skylark of Space” featured interstellar travel and dealt with megaforces and megadistances. It was an example of what came to be called “super-science stories” and Smith made it his specialty. Naturally, others followed the trend, and Campbell did so from the start. He quickly became second only to Smith in the super-science field.

There was a difference, though Smith could not change. He remained super-science to the end. Campbell could change and did. He wanted to write science fiction less in scale and more in introspection, less with ravening forces and more with puzzling mind.

He even changed his name for the purpose, writing a series of stories as Don A. Stuart. (His first wife’s maiden name was Dona Stuart.) The first Stuart story was “Twilight” which appeared in the November 1934, Astounding Stories, a sad, haunting tale of the end of humanity. It proved an enormous hit, and instantly began the change of making science fiction smaller in scope and deeper in thought.

He wrote Stuart stories predominantly, thereafter, until he published his towering masterpiece “Who Goes There?” which appeared in the August 1938, Astounding, and which was reprinted in the first book of this series.

By October 1937, however, he had been appointed to an editorial position at Astounding and, within a few months, he was in full charge. His first significant action was to change the name of the magazine, a change which reflected his thinking. He wanted to get rid of words like “amazing”, “astounding”, and “wonder”, which stressed the shock-value and superficiality of science fiction. He wanted to call the magazine simply Science Fiction, thus merely defining its scope but allowing him to fiddle with the details at will.

Unfortunately, he was too late. Columbia Publications had already registered that name, and a magazine so-named (not at all successful) eventually appeared in the spring of 1939. Campbell was therefore forced to make only a partial change. With its March 1938 issue Astounding Stories became Astounding Science Fiction.

As editor, Campbell was a phenomenon even greater than he had been as a writer. He held open house and anyone who might conceivably help him achieve his aims was welcome. When, on June 21, 1938, a frightened eighteen-year-old, named Isaac Asimov, appeared with his first story at Street & Smith Publications, Inc. (which published Astounding), he was invited into Campbell’s office, and Campbell spoke to him for an hour and a half.

I say “spoke to him” not “spoke with him”, for Campbell’s idea of a conversation was to launch into a long monolog. Oddly enough, though, he was no bore. He was an inexhaustible fount of odd and exciting viewpoints, novel thoughts, and endless story ideas.

He had an unfailing eye for potential. He rejected my first story at once. He had said he would read it right off and had kept his word (very unusual in an editor) so that it was mailed back to me the very next day. However, he saw something in it, or in me, or both (Heaven only knows what it could have been at that stage) and encouraged me to continue writing. I could see him whenever I came in and he was unfailingly courteous and encouraging, even as he continued to reject my stories, until I had learned enough about writing (from actual experience at it and from listening to him) to begin selling.

I was not the only one. He talked to dozens of writers and slowly taught them that science fiction was not about adventure primarily, but about science. It was not about rescuing damsels in distress, but it was about solving problems. It was not about mad scientists, but about hard working thinkers. It was not by writers who had a facile hand with a cliché, but it was by writers who understood science and engineering and how those things worked and by whom they were conducted. In short, he found magazine science fiction childish, and he made it adult.

The wonder is that he was successful in doing so. It is hard not to view the world with cynical eyes and, to the cynic, improving the quality of an object and reducing its sensationalism, is the quickest road to bankruptcy one can imagine. Somehow, Campbell managed. As Astounding improved in quality, it also improved in general acceptance and in profitability.

The true test came in 1948. Pulp fiction had been fighting a losing battle during the 1940s. World War II had created a paper shortage and a combination of the draft and of war-work had reduced the number of writers. (Campbell’s other magazines, the wonderful Unknown, succumbed to this.) In addition, comic magazines had come into being, had proliferated unimaginably, and had begun to draw off younger readers delaying and, sometimes, totally aborting their eventual reading of pulp fiction.

In 1948, Street & Smith, which had been the most prominent and successful of all the pulp fiction publishers gave up and put an end to all their pulp magazines – all but one. Astounding Science Fiction, and only Astounding Science Fiction, continued. It was John Campbell who had made that possible. Had he not been there for ten years, improving Astounding and making it the phenomenon it was, the magazine might have ceased publication at that time and magazine science fiction might have been dead.

Who were the authors with whom Campbell worked? Some had already published stories in the pre-Campbell era, and Campbell cou

ld work with them, either because they were already thinking along Campbellesque lines or because they could do so once they were shown what it was that Campbell wanted. Outstanding among these were Jack Williamson, Clifford D. Simak and L. Sprague de Camp.

For the most part, though, Campbell found new writers. The July 1939, issue was the first issue that was truly marked by Campbell’s thinking and Campbell’s new authors, and it is usually considered as the first issue of “the Golden Age of science fiction”.

As its lead novelette, the issue had “Black Destroyer”, the first science fiction story written by A.E. van Vogt. It also contained “Trends” by Isaac Asimov, “Greater Than Gods” by C.L. Moore, and “The Moth” by Ross Rocklynne. All four of these authors have novellas in this collection. Van Vogt and Asimov are perfect examples of what are still referred to as “Campbell authors”. Moore and Rocklynne had published before, but Rocklynne became a Campbell author too.

In the very next issue, August 1939, there was a first story, “Life-Line”, by a new Campbell author named Robert A. Heinlein. He and van Vogt were the mainstays of Astounding for several years and were the science fiction “superstars” of the time. Indeed, Heinlein remained a superstar and the pre-eminent science fiction writer until his death a half-century later in 1988. We would certainly have included any of several Heinlein novellas in this book were it not for difficulties over permissions.

Another particularly great Campbell author who does not appear in this collection is Arthur C. Clarke, whose first science fiction story was “Loophole” which appeared in the April 1946, Astounding. Unfortunately, his 1940s output was almost entirely in the short story length.

The Mammoth Book of Golden Age SF

The Mammoth Book of Golden Age SF